The career of Rick Stevens has evolved in much the same way his paintings do. Stevens takes his inspiration from the natural world, approaching his paintings with spontaneity and transmitting the feelings evoked by the landscape with immediacy and improvisation, an approach he compares to the jazz music often playing in his studio. Stevens spends quite a lot of time in nature where he has found his spirituality, his connection to the natural world and astonishing beauty that he translates into his raw and unconventional style. Here, he shares his his history with plein air painting, his resistance to categorization, and the surprises one may find in the woods.

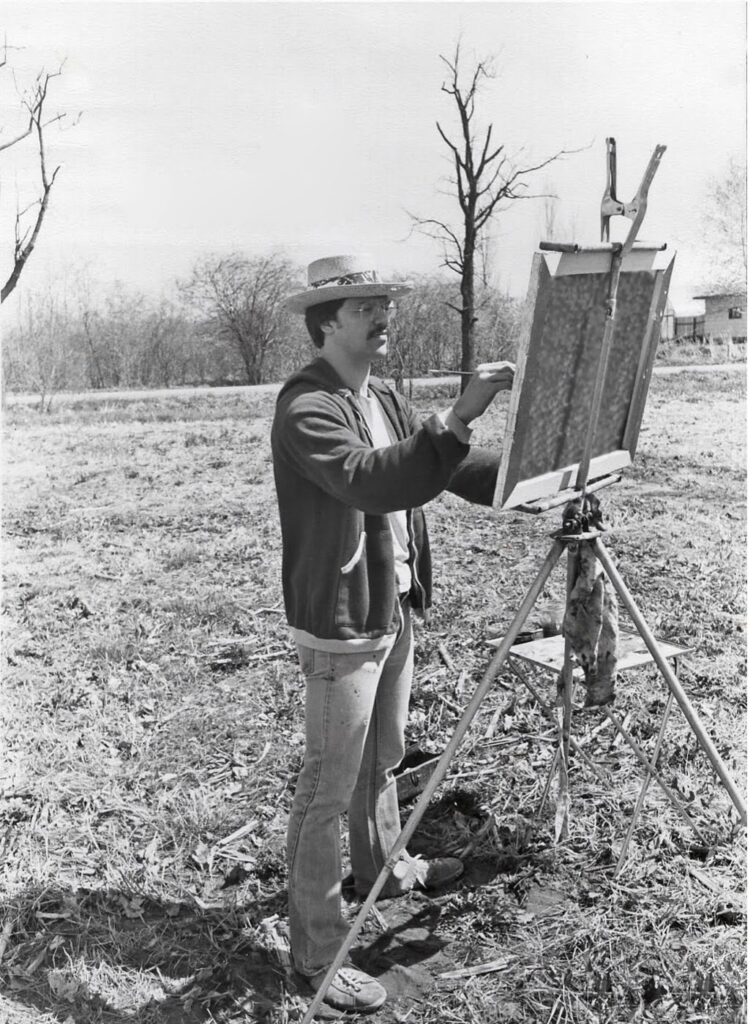

I grew up watching my father, Jim Stevens, paint landscapes. Naturally, my first attempts at plein air painting were on ventures with him. He was a self-taught painter with natural ability, a strong connection with the natural world, and a knack for inventing things. He constructed a portable easel out of galvanized steel pipes, which I gratefully put to good use for years. The tripod detached from the body and were adjustable for height.

Painting outdoors is a great practice. I highly recommend it to developing artists. Still, I’ve never fully embraced the label “plein air painter” for myself. Even during periods when I did a lot of outdoor painting the term never quite fit. Labels tend to be limiting, especially when you have a tendency to follow impulses over conventional rules. My own work resists neat categorization.

By the time I complete one of my plein air paintings, I have spent far more time working on it in the studio than whatever time I spent painting outdoors. Whether it still counts as plein air painting is open for debate, but I’ve never been a purist about such things.

Plein air painting often includes an element of adventure. Besides my setup for oils, I like to bring a sketchbook and am always gathering reference material by taking photos, whether with a professional camera or the camera on my phone. I often find myself bushwacking through off-trail terrain: along rocky streams, through dense undergrowth or up steep inclines that can push my physical limits. At times it feels like a sport, although a solitary and non-competitive one.

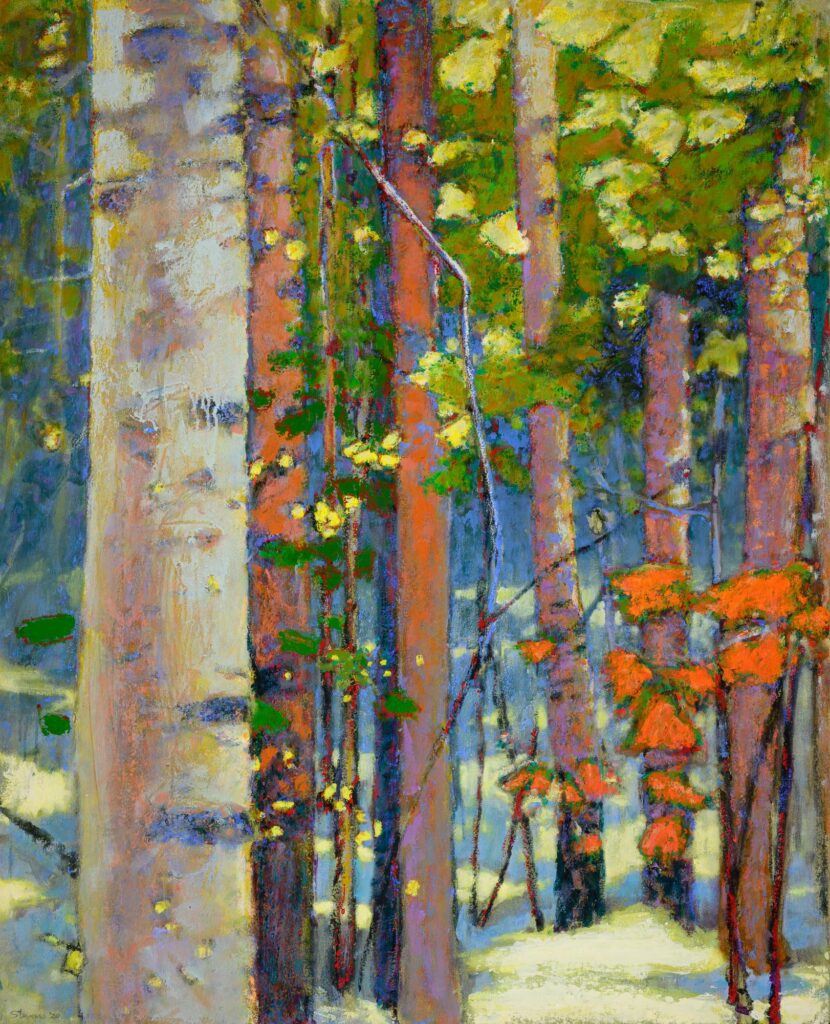

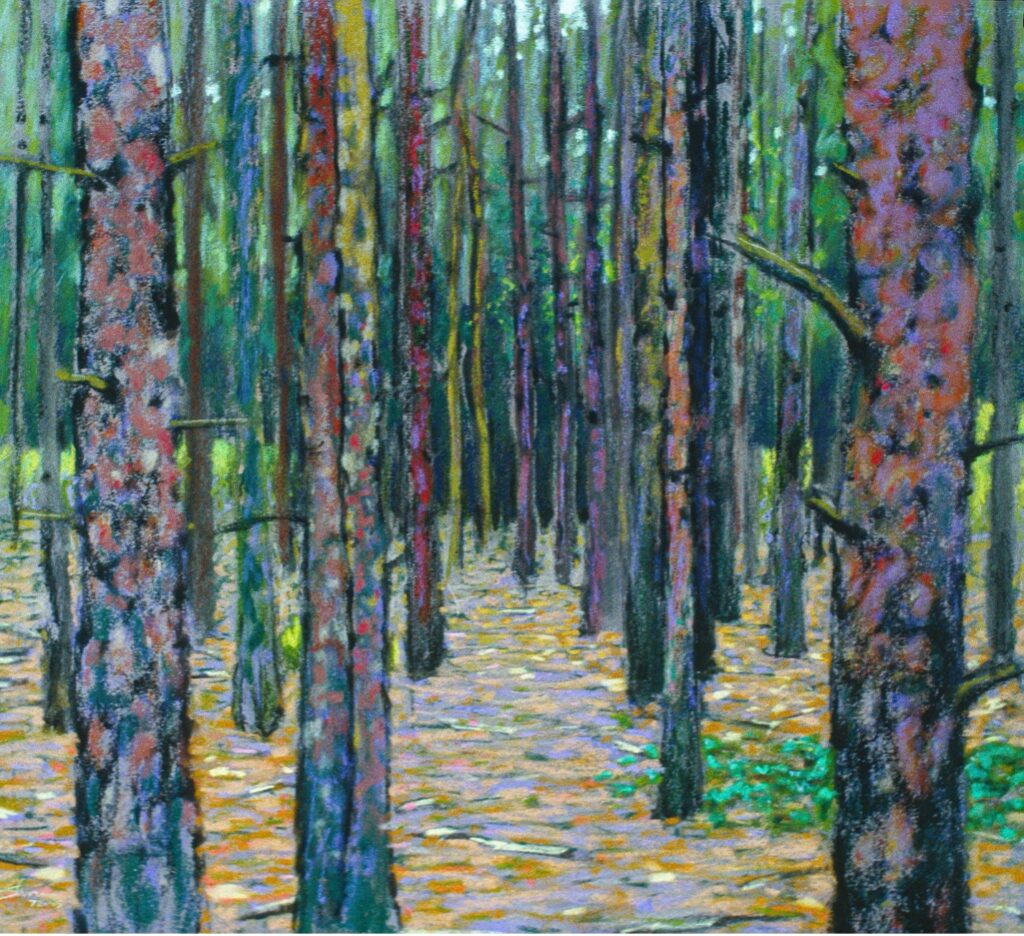

As an artist-in residence at several national parks, I’ve been privileged to paint some truly spectacular locations. I’m also drawn to less dramatic, intimate spots that I can revisit in different lights and seasons. Just ‘looking’ is an underrated practice in cultivating a vision for your artistic direction. The Japanese term Shinrin yoku, or “forest bathing” captures this well: the idea of absorbing the landscape through the senses, allowing the mind to quiet.

For a landscape painter, strengthening visual memory is especially important. Experience and practice will build facility with your materials to be able to summon those impressions later in the studio. While a painting that’s well executed is pleasing and satisfying, it isn’t everything. There are artists who push the boundaries of the pictorial language with a willingness to reveal the struggle untethered from formal training. There’s a raw energy in the art of children, in outsider art and indigenous art.

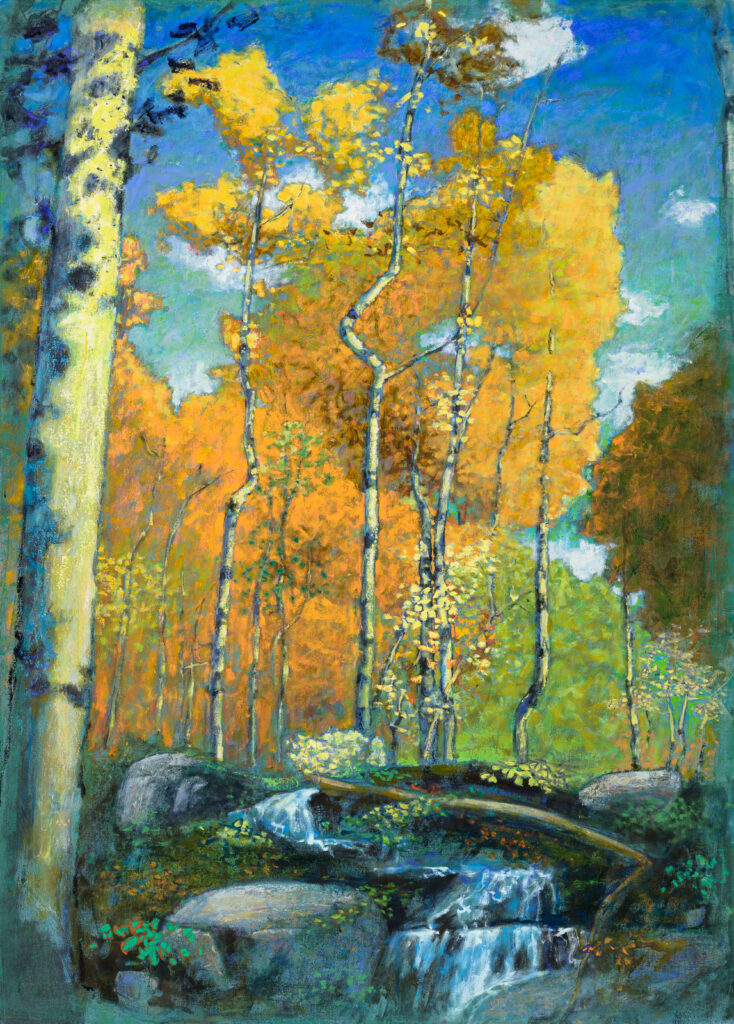

Pastels have been an important medium for me both in the studio and for plein air. While they are usually considered a drawing medium the application can be more like painting. My oil painting has been informed by how I use pastels, particularly the layering; and how I use pastels are a lot like how I paint in oils. Each medium has given me insight into the other.

Over the decades, my approach to painting small landscapes – plein air or otherwise – has evolved. Currently I’m mostly working larger scale, but recently I’ve been working up small landscapes from sketches and what I call my “digital studies.”

At 22, early in my development as an artist, I had a spiritual awakening while on a plein air excursion in the forest. It was while I was with my dad one weekend at our hunting cabin in Michigan. As he went to his blind for bow hunting deer, I left with my pastels to do plein air work. My intention was simple: to remain open to whatever moved me and to capture the essential with my pastels. I felt deeply inspired. By the time the sun began to set, I was frantically working, abandoning one sketch to begin another. Everywhere I looked I was struck by pure beauty and was literally overwhelmed. I finally let go of the effort to capture or contain it and surrendered to a realization that the “I” that was observing was not separate from what I observed. My whole identity melted into the Whole of the experience. It was beyond an intellectual realization, but a complete immersion, a temporary loss of ego identity. At the time I had no context for such an experience and kept it to myself.

Later, I would learn that such states of mind go by many names and descriptions across spiritual traditions. It was a seminal moment for me and set me on an artistic direction as well as a spiritual journey. A year later I became involved with a spiritual teacher from India (Swami Amar Jyoti) and took an unsanctioned retreat for a year in that same forest, a time of deep reflection and of developing a vision artistically and spiritually.

When people think of plein air painting, they often think of oil or acrylic setups. But plein air can be practiced in many forms: watercolor, pastels, or simple line drawings in a sketchbook. Frederick Frank’s book The Zen of Seeing speaks beautifully to this, emphasizing the experiential side of art making.