“As an artist you learn everything about the language you work in

and you take the vocabulary and make it your own.”

—Leon Loughridge

Leon Loughridge is a painter and printmaker, translating his plein air sketches and watercolors into captivating reduction wood blocks, hand-printed on a 1920 Vandercook Flatbed Letterpress through his publishing company in Denver, Colorado. Wood block prints are a type of relief print made by carving a block of wood, inking the surface with a roller, and transferring the ink onto paper. The process—carve, ink, print– is repeated with each new color addition, up to 20, in the case of Loughridge.

In an interview with Ann Korologos Gallery in Basalt, Leon Loughridge shares his process, challenges, inspirations, and how he relates to his final work.

The images below were provided by Loughridge to give a sense of the process, using his wood block print, Aglow, as the example. The initial watercolor “sketch” done en plein air was re-done as a more detailed color study to act as a “road map.” Three blocks were used, and color runs 2, 8 and 9 are shown, followed by the final image

My grandmother was always meeting artists, and would invite them to come to the house in Santa Fe and meet and talk. As kids, she would always entertain us in the summer with arts classes. At that young age you see a lot, and don’t realize all that you’re absorbing in the arts, and later in life you all of a sudden realize that you learned a lot. I went to Colorado Institute of Art for college for drawing and painting when I got a draft notice. The choice was to go to Vietnam or Germany, where I ultimately spent 3 years. I traveled around in Germany and my commander allowed me to bring pen and ink everywhere we went, which was a natural transition into etching.

I was then stationed in Stuggart, where I bought a small press and had it shipped to the US where I moved to Carbondale and lived at the Ranch at Roaring Fork. Eventually, I bought the Vandercook press, my current press, and ‘went from the dark side to the color side’ from etching to wood block prints.

Leon Loughridge, “Autum Stroll, Mt Sopris,” Watercolor on Paper, 14.5 x 21.5 in

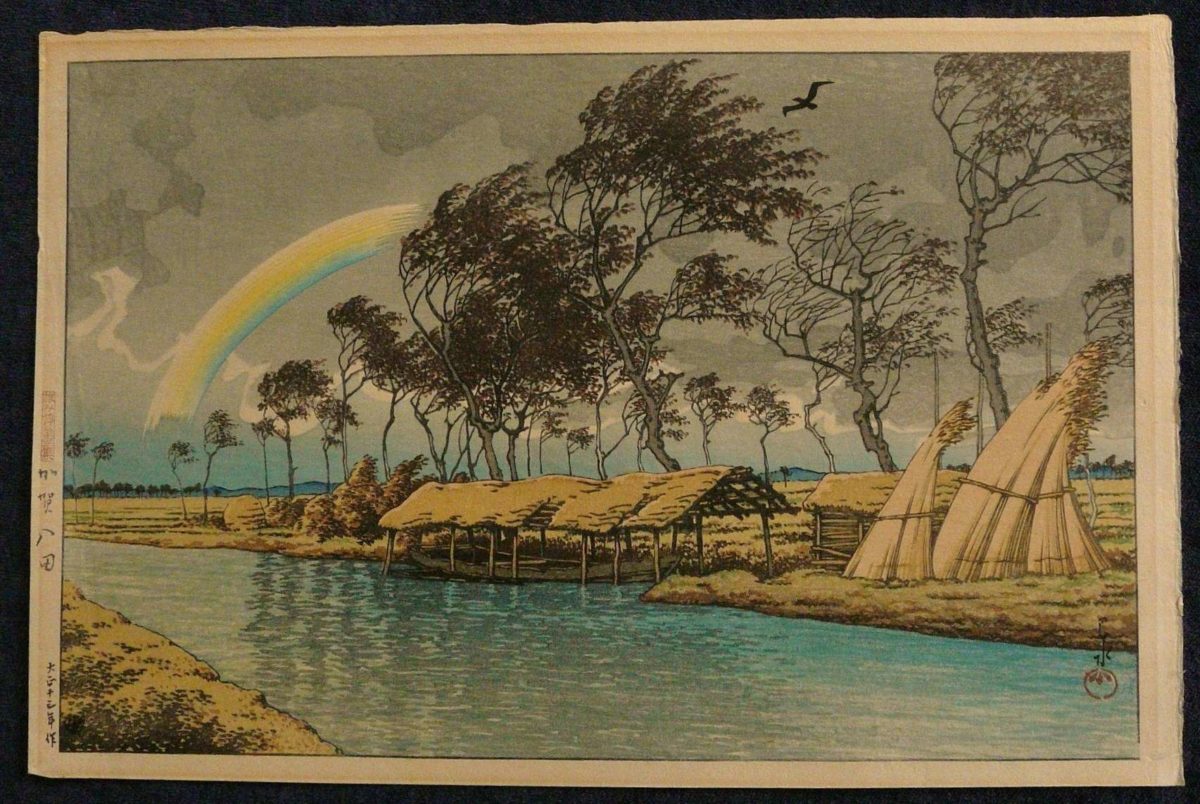

I have been really inspired by the Japanese wood blocks, especially Hasui Kawase and Hiroshi Yoshida, both considered masters of the shin-haga movement. The coloration is just phenomenal– they are almost a watercolor through the process used. There’s a beautiful transparency to the colors, and [wood block prints] are very similar to watercolors in feel and look.

Kawase Hasui, “Autumn Rainbow at Hatta, Kaga,” 10.2 x 15.2 inches. Image provided by Wood Block Print

Then you get into the older Ukiyo-e [a genre of Japanese art] from about 1750-1867. The prints are amazing, technically, with what they could do. They had to be incredibly creative because of the government restrictions on what they could print, how they could print, and what they could sell them for. We really have it easy in the colors we have available to us, and the lack of restrictions.

Because of that I tend to obsess and get carried away with color runs. What could be done in 6 color runs I’ll do in 18-20.

Leon Loughridge, “Wild Horses Below Mt. Blanca 24/26,” Woodblock Print, 8.5 x 7 in

The more comfortable one becomes with a process, the more fluid you can be with how you work with it. If you’re stuck on Dick and Jane, you’re doing a one-color wood block, but if you can really move beyond the processes, it really becomes fluid. As an artist you learn everything about the language you work in and you take the vocabulary and make it your own.

Usually what I’m going for is what stopped me; what caught my eye; what about the scene was so dramatic. With small sketches I can quickly pull out my ‘folio — lighting on the hillside, the rain showers coming down– small sketches or watercolors quickly capture it. It’s not the amount of leaves on the tree that catches your eye, but the light arrangement. It’s almost like a stage setting: you set the scene to capture its drama.

Sketching outdoors is essential to gathering your creative ideas to be built up and explored in the studio. I love to sketch or watercolor on location, and don’t rely on photographs. I’ll take them, but I often forget to look at them, as they are often sterile. When I’m sketching—6 x 8 inches– I work small to capture the characterization of the scene— almost a cartoon. Working that small, you can quickly capture the essence of the scene that you’re painting. You simplify shapes: a hillside will become dark blue/green, which builds an abstract quality to the scene and that quality gives an image its dynamism. So, with sketching, you tend to catch the essence and give up the details and trivia that don’t need to be added.

To me, the wood blocks are paintings. They are wood block paintings. When I’m carving and proofing, that becomes very spontaneous. I usually have a watercolor in front of me— usually not very big. It’s the original watercolor I did on site, which becomes my roadmap to how I’m building and progressing my colors.

In the studio, with the Vandercook Press, I am layering colors repeatedly to build the forms, almost as I would a watercolor, but each layer is a wood block or a reduction of a block. As I would with watercolor, the printing process usually has me working from light to dark, starting with the lightest values and start moving towards the darks.

I typically start with 40 sheets of paper. Of the 40, 5-10 will be proofs where I experiment with how to put the ink on. When you stand back 10-15 feet, they all look the same, but when you walk up on them and look at the detail, you’ll see the differences. I usually end up with editions of 20 or so.

What I put into the painting— it’s between me and the painting. And when I’m done, I’m now just the viewer. The trick is to be able to give the viewer an entry into the scene, get them involved somehow, and let them attach their own history and feelings. Usually my feelings as a viewer are the same as others, but sometimes you get an outside view and have a conversation about it. It really becomes fun because you and another person start a conversation and learn about each other.

The works of Leon Loughridge are exhibited nationally and collected by numerous museums including the Denver Art Museum, the Denver Public Library, Wichita Art Museum, and the Colorado History Museum. Loughridge was selected to be the featured artist for the 2005 Colorado Mountain Landscape Exhibition and Sale, and his work is on display in the Coors Western Art Exhibit and Sale from the years 2014-2018. His work is available at Ann Korologos Gallery.